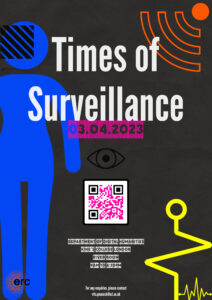

Times of Surveillance

Monday 3rd April 2023,

River Room, King’s College London

9:00 – Registration and Coffee

9:30 – Welcome and Introduction: Vita Peacock

9:45 – Keynote Lecture: Sun-ha Hong

10:30 Times of (health)care

10:30 – Meyer and Albrechtslund, Timely Responses: Using Surveillance Technologies to Support Dementia Care

10:50 – Claire Dungey, Surveillance in the family: monitoring, care and temporality in Germany

11:10 – Liam Simmonds, Generating Self-Knowledge for Health/Pleasure Outcomes in Recreational Drug Consumption Practices through Digital, Social, and Ethical Surveillance

11:30 – Discussion (Discussant and Chair: Kenni Bruun)

12:10 Real-time Monitoring

12:10 – Alice Riddell, Citizen app: The digitization of crime and the temporality of personalised security

12:30 – Andreas Stoiber, At the intersection of scientific knowledge and humanitarian action: Space-Eye and the temporalities of satellite surveillance/sousveillance

12:50 – Karolina Kupinska, Temporal Control as a Result of “Small Act” Surveillance During COVID-19 Pandemic in Xiamen, P.R.C.

13:10 – Discussion (Discussant and Chair: Claire Dungey)

14:30 Time is money

14:30 – Martin Webb, Putting the selfie to work: Image making and work/time discipline in the margins of the Indian state

14:50 – Martina Eberle, “Your voice counts” – Managing response to resistance through surveillance regimes: digital people analytics platforms as instruments of governance in corporate environments

15:10 – Lake Polan, Sin, Intimacy, and Disavowal in the Internet’s Business Model

15:30 – Discussion (Discussant and Chair: Matan Shapiro)

16:00 Policing (and) the Future

16:00 – Sophia Goodfriend, The Banality of Surveillance: On Maintaining Israel’s Surveillance State in the Occupied Palestinian Territories

16:20 – Carolina Sanchez Boe, Temporal Experiences of Digital Detention and Extractions of Time for Profit. Electronic Monitoring of Asylum Seekers in the USA.

16:40 – Becky Kazansky, Resisting the violent temporalities of preemptive surveillance: strategies and their tensions

17:00 Discussion (Discussant and Chair: Vita Peacock)

17:30 – 18:30 Concluding Discussion (chair: Vita Peacock, discussant: Sun-ha Hong)